“I hear it in the deep heart’s core,” writes the speaker of Yeats’s beloved poem, “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” when conjuring a mental image of home.

For all the emotional weight it carries, home can be a startlingly ethereal thing. Home changes; it is lost, found; remnants of it circle through unfamiliar spaces; images of it surface in the mind. It is this transient quality that has prompted generations of poets to translate the experience of home into lines and words, to identify what, exactly, home is. While it might often become a means of exploring home, poetry is also deeply interconnected with home’s opposite: displacement.

The act of description necessarily implies distance. When we are fully present in a moment or feeling, we simply experience it, rather than attempting to describe, record, or understand. As soon as a poem begins to describe home, it leaves a record of the speaker’s displacement: the fact that the poet is writing about home implies that they are not fully present there. Rather, the poet is engaged in a kind of longing—because isn’t that what poetry is?—a kind of reaching towards the image of home.

The poems dive into this home/displacement dynamic, exploring shifting borders and disappearing communities, the tension between actual and emotional homes, the lives of homeless citizens, home in the context of the family and the struggle of being unable to return to home, and the ability of home to bear witness to personal history. In their search to define home, these poems push the boundaries of mediums: Jennifer Hasegawa brings her work to life through video, and Ryan Clark conducts homophonic translations of anti-immigration bills and archival material. Both Clark and Alfredo Aguilar complicate home by exploring not only the emotional aspects of home, but also the conflicts imposed by nations and borders. Emilia Phillips and Marcus Amaker introduce the concept of the body as a home, whether through the lines, “I met myself again and again / in the mirror, which is the farthest distance one travels / without being with oneself,” or through a discussion of homelessness.

When considered in this historical moment, the poems take on additional weight, providing powerful commentaries on the unique meaning of home during a global pandemic. I encourage readers to consider both the personal engagements with and unique depictions of home in each poem, as well as the ways in which these perspectives shed light on the comforts and challenges of home during quarantine. While the act of description might imply distance, it can nevertheless bring us together through shared experience, at least for a moment, drawing us nearer to home “in the deep heart’s core.”

Read the poems here!

—Isabel Prioleau, Halsey Institute intern

Images:

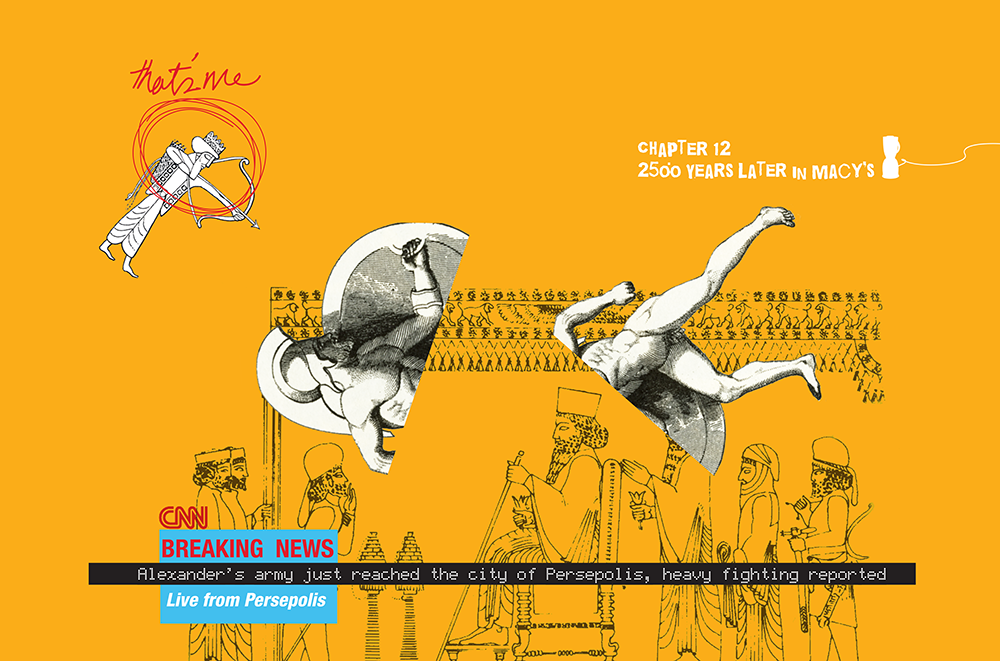

top – Hamid Rahmanian, 2500 Years Later, 2006. From the Multiverse: To Myself with Love series. Archival digital print, 11″ x 17” Image courtesy of the artist

middle – Jiha Moon, Familiar Faces, 2015. Acrylic on Hanji paper mounted on canvas, 28” x 44” Image courtesy of the artist