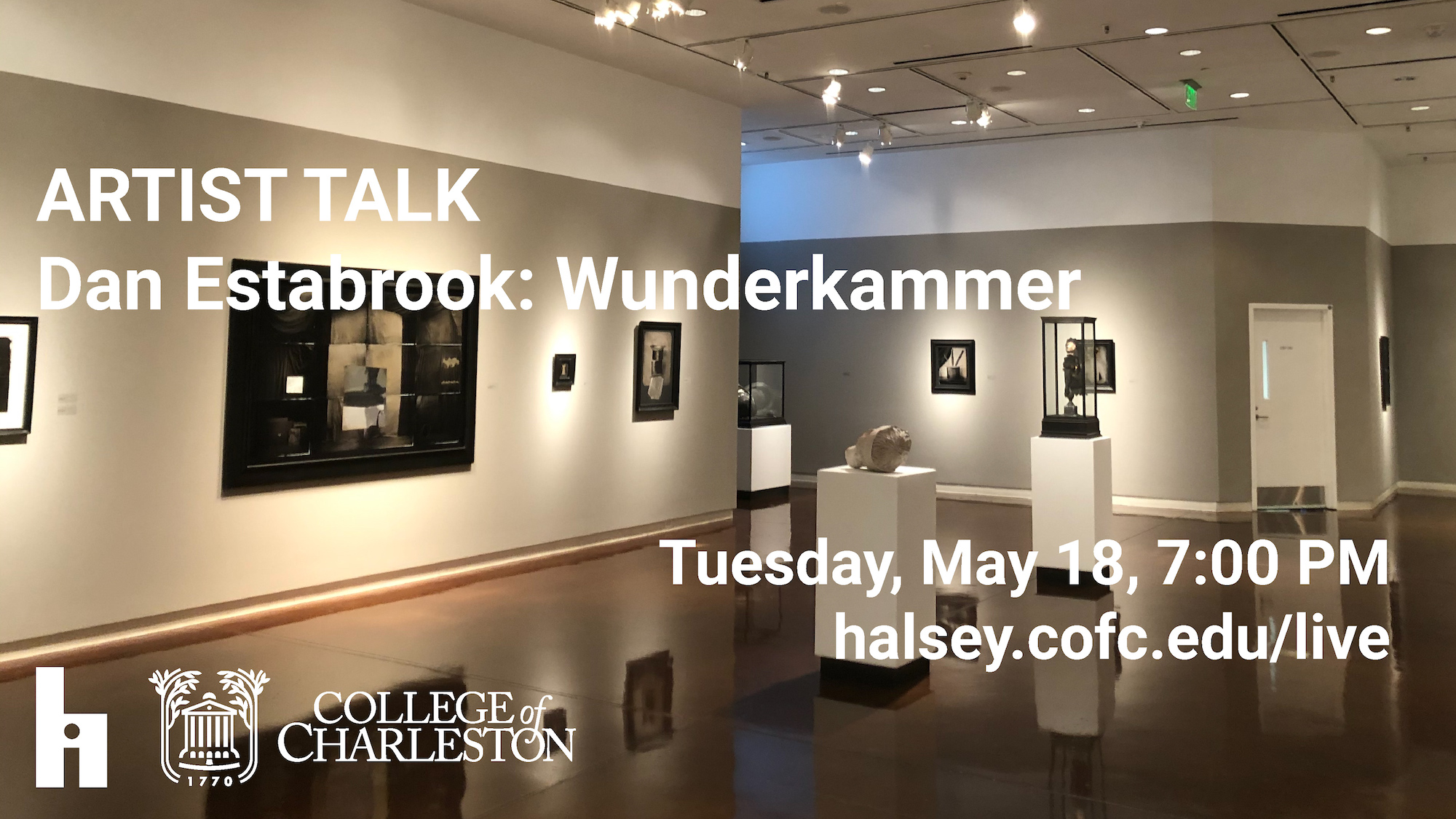

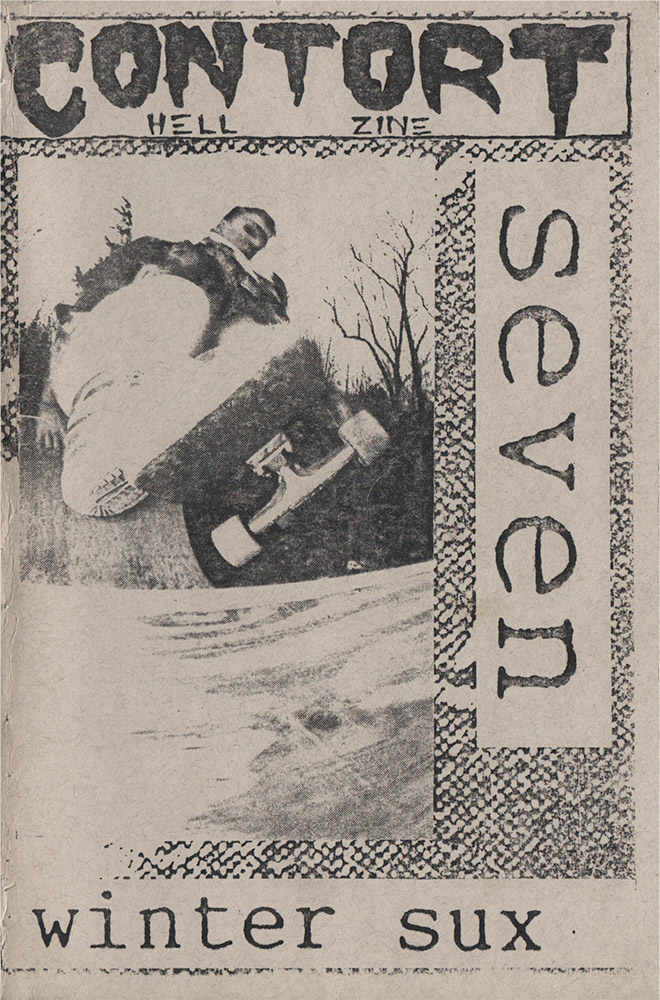

Dan Estabrook never intended on becoming a photographer. This is surprising, of course, because Estabrook’s exhibition, Wunderkammer, and his artist talk with the Halsey Institute are centered around his works as a photographer. As a young art student, Estabrook was passionate about painting, drawing, and sculpture — photography was reserved for taking pictures of skateboarding. Estabrooks’s first brushes with photography were for a collaborative skate zine called Contort, where he was able to play with graphic design and learn how to shoot and print photos. However, art and photography remained separated in his mind. Young Estabrook hardly even considered photography to be art.

Contort #7. Source: skateandannoy.com

Then, he studied under Christopher James, a photographer famous for his alternative process photography. Estabrook fell in love. The alternative processes that James used combined Estabrook’s love for painting and drawing with photography, which felt exciting and gave Estabrook an opportunity to learn about something new. However, at the completion of his undergraduate thesis in photography, he still felt that he was grasping for something more.

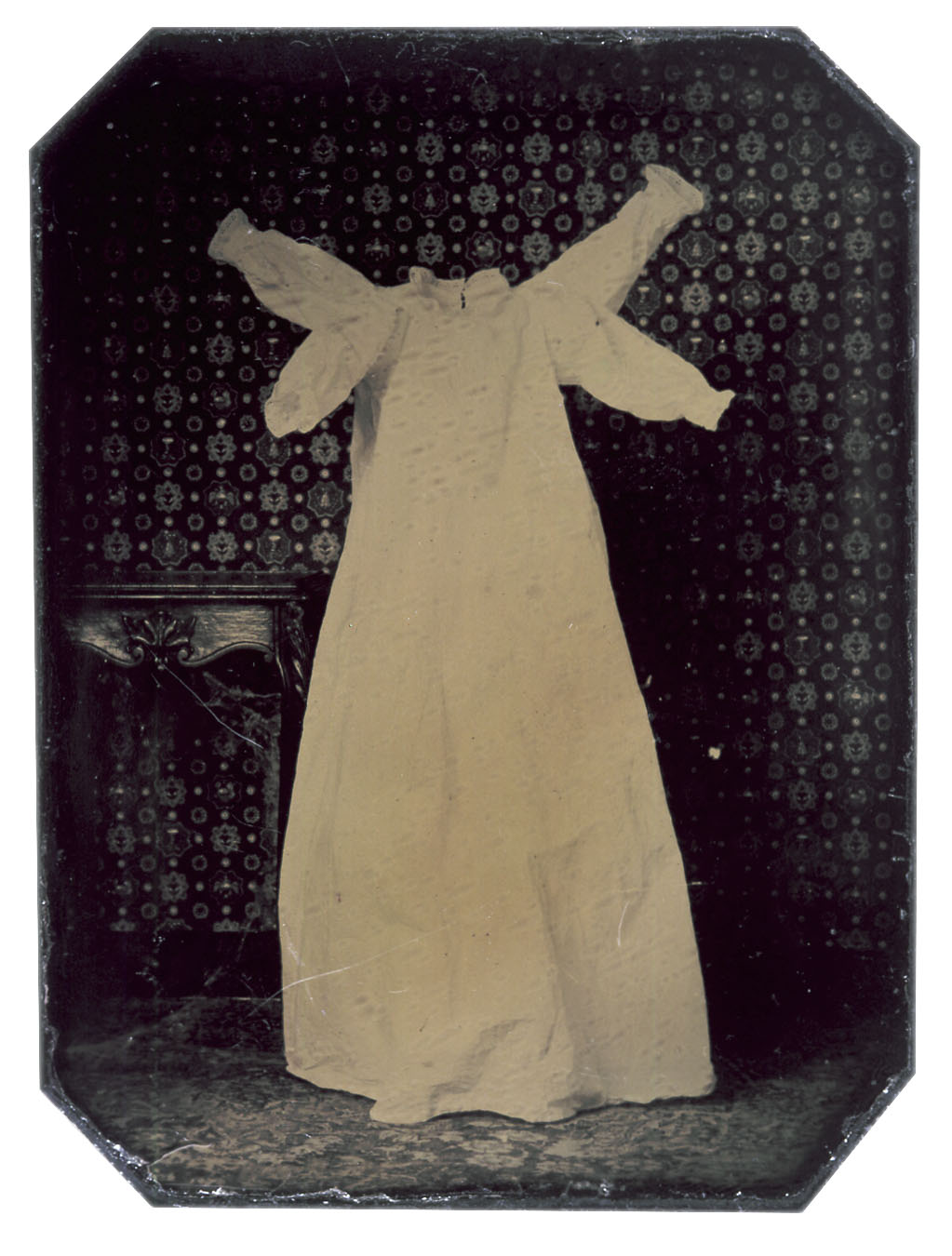

Estabrook decided to go to graduate school for photography. During this time, he says, he was struggling. So, he found himself looking back on what he enjoyed most about photography. Up to this point, Estabrook was collecting 19th century tintypes; mostly tintypes of babies in white baptism dresses. What really fascinated him about the babies in the white dresses was that, while most of the children in the tintypes were alive, some of them were dead. The white dresses were being worn to celebrate life and to commemorate death. This duality was the profoundness that Estabrook had been looking for in photography all along.

Tintype featuring a baby in a baptismal gown.

In 1993 Estabrook created his own version of the baptism dress in the piece Untitled Angel, which is currently on view at the Halsey Institute. It is a tintype, printed in the traditional 19th century process. The piece mimics the form of the baptism dress but has two extra arms and no head. It is the smallest work in the exhibit, roughly the size of the real tintypes that Estabrook loved to collect.

Dan Estabrook, Untitled (Angel), 1993. Tintype.

Dan Estabroook has had a fascinating artistic journey. The rest of his artist talk, however, deals with the questions that he faces in proximity to his work. In practicing antiquated forms of photography, Estabrook raises some interesting questions about truth. Usually, in this technological age, we consider ourselves more equipped to discern fact from fiction. However, Estabrook points out that our technological advancements have increasingly allowed us to fabricate truth, whether that be through digital edits, filters, or photoshop. There is a certain authenticity that can be found in 19th century photography, however, because these photographs were made in an age before digital altercations were possible. These 19th century photographs are, to Estabrook, considerably more resistant to change.

If you would like to learn more, you may find Dan Estabrook’s artist talk at https://halsey.cofc.edu/watch/.

-by Meg Carroll, Halsey Institute intern