For her exhibition Over There and Here is Me and Me at the Halsey Institute, Andry is using these explorations of stereotypes to see how gentrification develops and is sustained. By looking at specific tropes like violence and drugs, she examines how such concepts are used as weapons to devalue communities, forcing out their long-time occupants and allowing these areas to become gentrified.

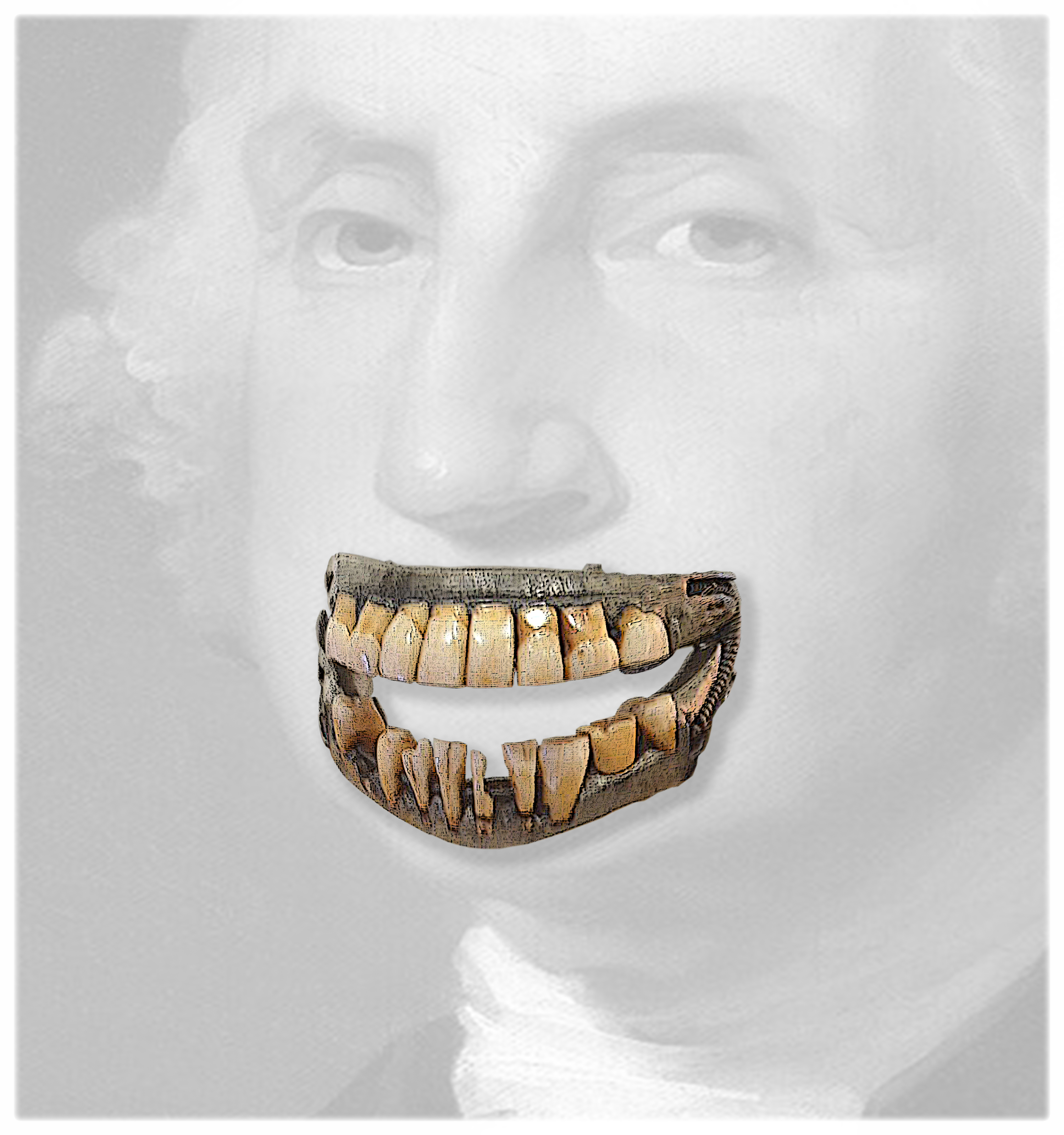

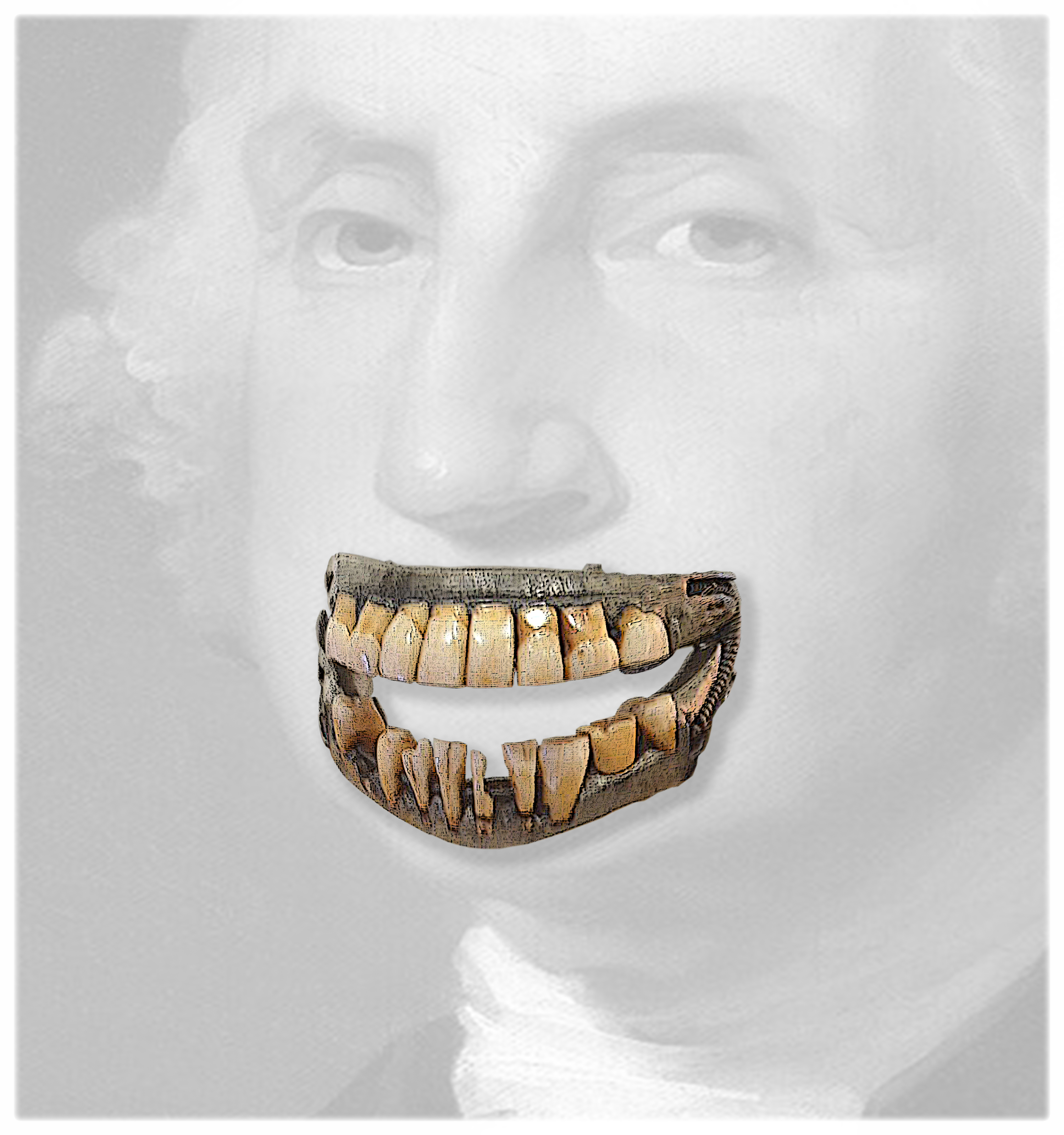

What reward is offered to Quashie’s audience for gaining awareness of such a heinous reality? Is this a topic for discussion? In considering something that embodies social issues that are so very challenging, what value is provided for us, as audience, in responding to such an image? In confronting the contextual ugliness (made seductively attractive, even elegant by means of the use of technology mastering the incorporation and electronic manipulation of scanned photographic images, compelling graphic composition, employment of value, contrast, and digital manipulation), we inadvertently consider the comparable ugliness of aspects of our American social and cultural history and its slow, erratic evolution toward greater social equity and more highly developed conceptions of social justice. The Quashie images both remind us of an unfortunate past and represent to us the transformations, improvements, and technological advances of our own present moment. (These parallels convey the idea that although our culture has “changed,” those changes are as yet insufficient for achieving a goal of pervasive social justice.)

Quashie’s provocative art offers contemporary audiences opportunities to consider how we may seek to emerge from the convolutions of our own socially imposed collective conceptual quagmire of a metaphorical, cognitive “enslavement.” The images raise the question of whether we as a society are prepared to face the difficult truths Quashie’s potential “conversation” implies. Will we take the necessary actions toward attaining an enhanced, collective conceptual “freedom”?