Mireille Vautier | Rachel Wright | Adrienne Antonson | Pinky/MM Bass | Jon Coffelt | Leslie Kneisel | Nava Lubelski | Preston Orr | Susan Harbage Page | Marilyn Pappas

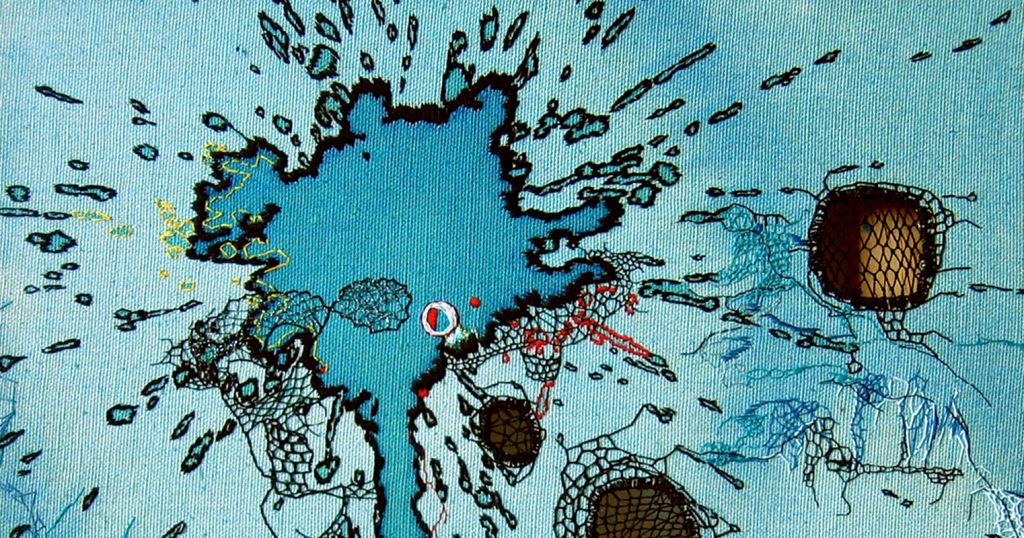

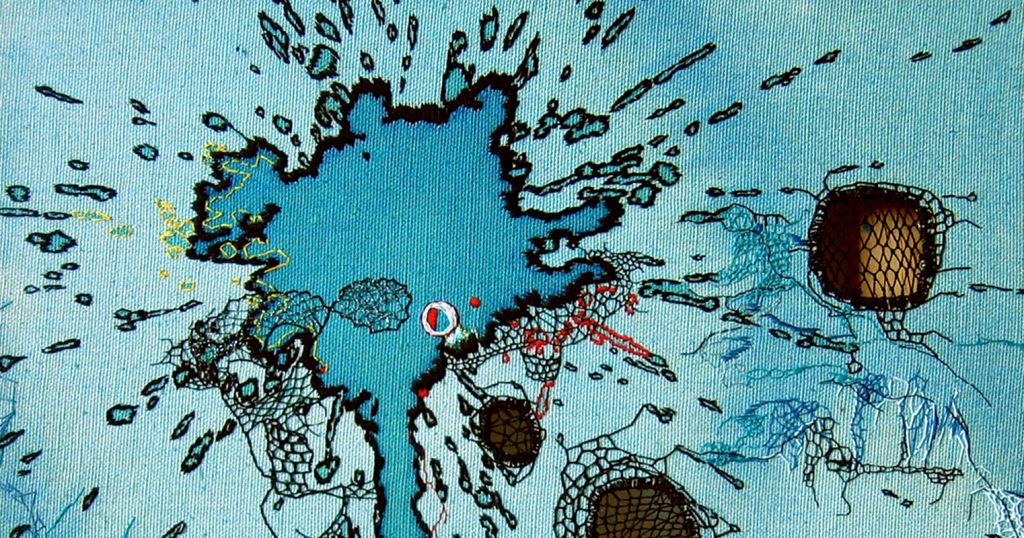

My embroidery work explores the contradictory activities of spoiling and mending, using a process of hand stitching over stains, spills and rips. The damage may have naturally occurred on used linens. In other cases, the “pattern” is created by giving vent to the impulse to destroy, tearing holes and spilling inks onto a pristine canvas. The subsequent repair is both aesthetic and structural, bringing the pieces back to a place of beauty while offering respect to the initial mark making and to the random actions or emotions that engendered them.

I’m interested in the embarrassment associated with graphic forms in the shape of stains. Stains are considered unredeemable or shameful and it has traditionally been a woman’s job to attempt to obliterate them through cleaning, hiding or discarding the ruined item. My process is one of resolving these stains through a reshuffling of traditional methods of repair – the use of mending tools to respond openly to the images, discovering and enhancing their formal qualities.

Through the deliberate making of spills and splatters, the work flirts with an update of Abstract Expressionism, overlaying this predominately male movement in painting with the historically feminine domestic medium of threadwork, with its traditional dependence on functionality, decoration and order. In this way it juxtaposes expressions of aggression with masochistic patience and sublimation. The work continues to play with the feminine and the sexual both through the focus on the graphic form of the traditionally embarrassing “stain” and, as in Spring at the Pole (2006), by adding peek-a-boo, lace-like inlays to 2-dimensional pieces, examining the canvas as a screen for the hidden space of wall bound by stretcher bars.

The work in Mend: Love, Life & Loss can sneak up on you. The materials of fabric and thread seem so innocuous. We associate them with the domestic and the feminine, and relegate them to the lesser realms of hobby and craft. At first these works do not seem to demand our abstract conceptual attention as so many works of contemporary art do. Instead of facing installations and conceptual puzzles, we are presented with hand-wrought objects that revel in their physicality. Every stitch and every manipulation of materials is time-consuming, repetitive, and tedious for the maker. The masochistic dedication to processing materials through time evokes the emotional patina of love, life and loss.

All of the artists in Mend speak of the funny or absurd, even the perverse, in what they do. First they take on the endless task of mending what has come undone: fixing stains, repairing ruins, reconnecting that which is broken, making visible to the outside what is hidden on the inside. All of this takes time, and dedication to a task that will never be completed. Instead of lamenting that condition, however, the artists relish the expenditure of time needed to craft their objects. They have the opportunity to see and experience their materials and their creation to an intimate degree. Comfort, and even pleasure, is gained through this connection. I would suggest that viewers can share this condition as well. We, too, know these everyday materials, and the quixotic desire to make and unmake our world as we find it. Who does not find things that they want to fix, recast, or even subvert? It may be most crafty to sneak up on these tasks with the familiar materials of the domestic.

During the 1970s and the early days of the feminist movement in art, domestic materials were a troublesome inheritance. On the one hand, women artists wanted to gain respect for materials and techniques that had been gendered feminine and therefore less important. Being labeled craft, or a hobby, was the same as being labeled not art. Judy Chicago decided to turn this bias on its head. Rather than argue against the unfairness of the gender stereotype, she decided to maximize the potential of those materials dismissed as feminine. Chicago used embroidery, ceramics, and sewing as the primary media of her Dinner Party (1974-79), in order make a monumental work that would speak to women’s history and lives. The result was a work of art that is among the most important of the decade. No matter how one might respond to her Dinner Party (and reactions still vary widely), there is no denying that it had a profound impact on discussions about the gender bias towards materials in both the craft and art worlds. Today it sits ensconced in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, a testament to its relevance in the debate about materials and meaning in contemporary art.

Another approach in the 1970s was to weld the emphasis on color, pattern and painstaking forming found in the domestic realms of embroidery, sewing, and quilting, to the abstract interests of contemporary painting. Joyce Kozloff and the Pattern & Decoration movement are most often cited in this regard. Unfortunately, this was a very short-lived experiment. The lesson to be learned here is that if one tacks too closely to the concerns of a dominant medium such as painting, any positive elements that the other media have to offer are simply usurped, without much credit.

So, how to balance such forces, and move beyond the polarizing politics of gender? The answer has two parts: one, create work that refuses to be one medium or one genre, and two, make work that appeals to both genders through the humor and pathos of shared human experience. This is both a refusal to be easily categorized or typed, and an unwillingness to be reduced to a debate along the binary line of “feminine” or “masculine”. I would argue that the mix of media employed by these artists, and their creation of works that defy easy genre categorization, is the primary tactic in their ability to confound gender stereotypes, and move beyond reductive readings. Because we are curious and engaged by the objects before us, both familiar and unfamiliar in their mix, we are more receptive to what they have to offer.

This brings us back to the issue of innocuous materials sneaking up on us, which brings to my mind the artist Eva Hesse. In Hesse’s work of the mid 1960s, such as Ringaround Arosie or An Ear in a Pond, the artist used materials like cloth, cords, and papier-mâché. With these pliable, organic elements, Hesse created works that evoke the body and prompt a tactile response. Cords protrude and hang, wires are coated and wrapped, and things bump and poke against surfaces. What Hesse relished about these characteristics were how contrary, unexpected and thus absurd they were given our expectations of what a work of art can do as it hangs on a wall. The organic, soft materials evoked fleshy surfaces, and the variety of materials allowed a range of textures and colors in Hesse’s objects. The artists in Mend mine their materials in just this way. The organic and pliable, like human hair or embroidery thread, are used to give texture and color to the imagery, shifting their objects from something known to something surprising and new. Hesse linked this moment of surprise to the absurd, and through that absurdity, a reengagement with the world around us. The world can once again surprise or delight us.

The large number of artists in this exhibition testifies to the widespread use of domestic materials in contemporary art today. We are not compelled to call these works craft, just because they are made from fabric or thread. Most of the artists would say they share the dedication to handmaking that is a primary feature of craft, but they are not creating craft objects with a utility. Artists also no longer have to justify using domestic materials, nor defend them against the charge of being feminine and not art. Instead, these materials are valued for what else they can bring to art, from evoking the body to foregrounding issues of process and time. Frequently these characteristics become intertwined, so that process and time are experienced via the body and what covers it. An artist well known for successfully using domestic materials such as fabric and thread to evoke memories, sensations, and emotions is Annette Messager. In Messager’s work materials wear the stains of time and memory, layering and exploring the emotions that create such marks. The materials bear a palimpsest of life experiences. The wonderful thing about palimpsests is that you can go back and change or subvert what was, mend that which turned out wrong, even try again. For the artists in Mend the process of making work provides the time to experience life, and perhaps mend what has gone before.

An essay by:

Dr. Marian Mazzone

Art History Department

College of Charleston

The MEND exhibition is supported in part by donations from Leilani DeMuth, Gil Shuler Graphic Design, Alloneword Design, Magar Hatworks, Worthwhile, RTW, Spinster Design, and the patrons and members of the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art.