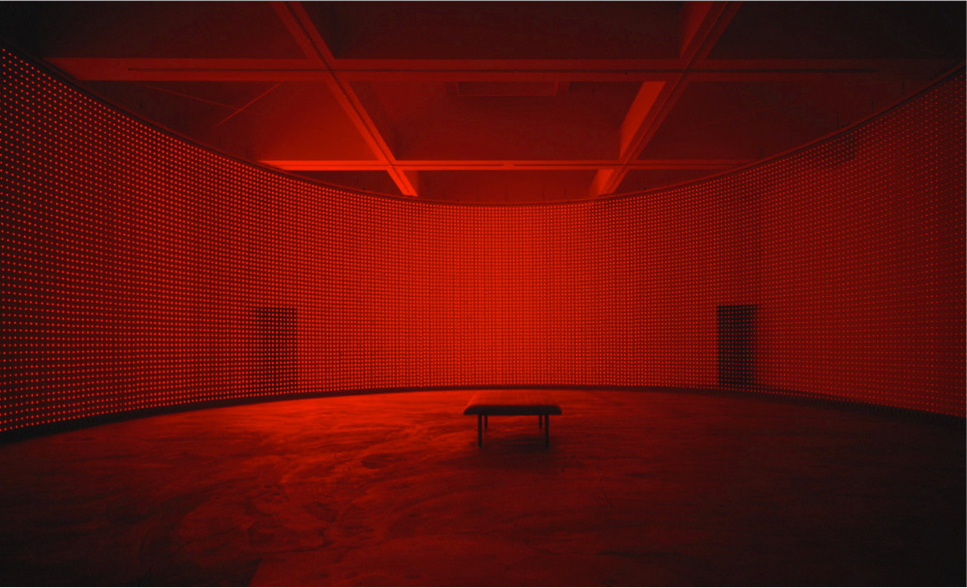

Erwin Redl’s current show at the Halsey Institute, entitled Rational Exuberance, showcases his ability to transform spaces into living works of art. Redl’s work forces viewers to enter an exhibit and confront a familiar space in unfamiliar ways, which installations have strived to do for decades.

Redl may be described as an artist who works in light, installation, and sometimes event prints. Art making after the “Digital Experience” has driven him to create works through many different media that challenge the viewer in how they see the work as well as how they interact with it. The manipulation of space, in regards to installation, has long been a shared concept between other artists that have worked with light. Redl has often spoken about his minimalist aesthetic and how large of a role it plays in his compositions, so it is interesting to consider the work of artists who pioneered the use of light and the manipulation of space when attempting to understand his methods.

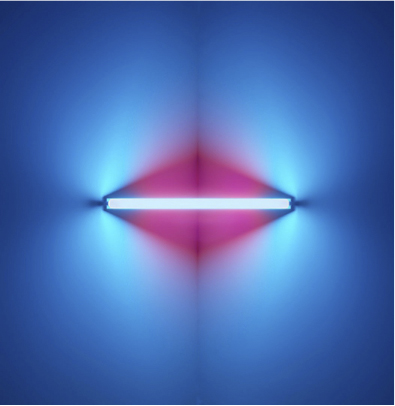

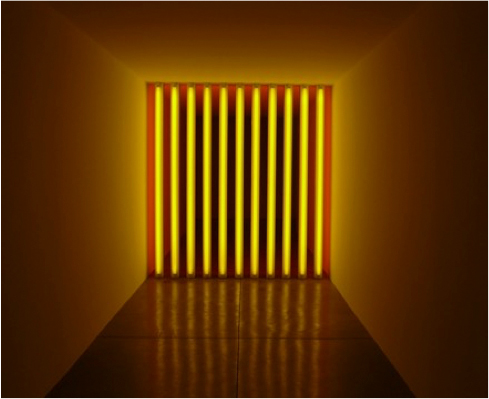

Dan Flavin was an American installation artist who worked with fluorescent light fixtures in the 1960s. His work was often site specific and incorporated lights that varied in scale depending on the place that it was set. These installations ranged from filling up a hallway with many multicolored lights, to employing one light in a single corner and using shadow to manipulate the rest of the room. Manipulating a small space to seem infinite, even if only in a corner, provided onlookers with one single focal point and enabled them to experience the room in a new way.

While Flavin used light in corners and hallways to make some of his most impactful work, others like James Turrell are known for working on a larger scale, hiding all traces of the light source.

Turrell is known for producing light tunnels, as well as light projections, which create spaces that appear thick and heavy but are only enhanced by light. The pairing of giant light forms with large spaces, presents the viewer with a work of art that seems larger than life. When one enters his spaces, it’s as if they are entering a world untouched by man. They enter a world of pure light, waiting to be seen and felt by others who have entered that other worldly realm. Turrell presents his viewers with an alternative to the busy world humans find themselves in today, inviting them into a mesmerizing abyss of color.

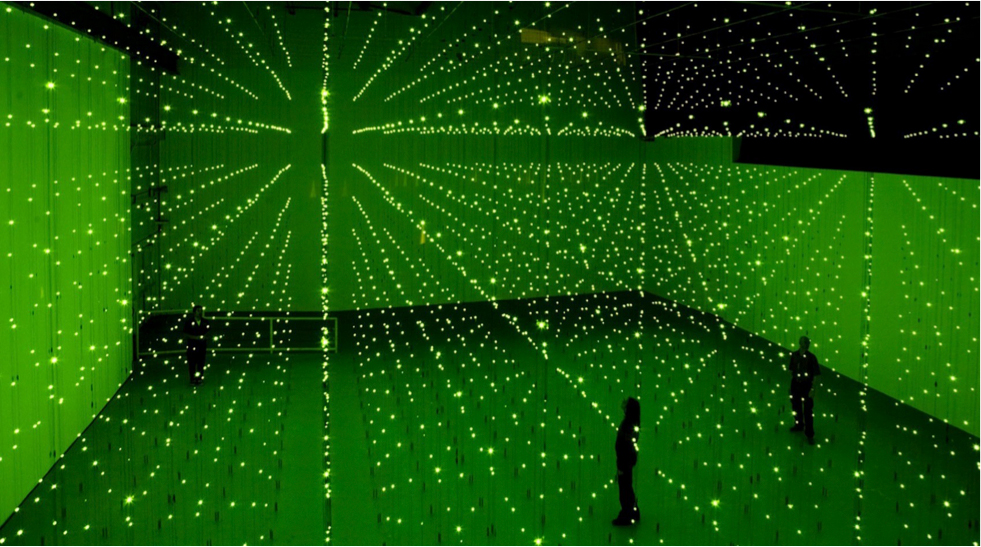

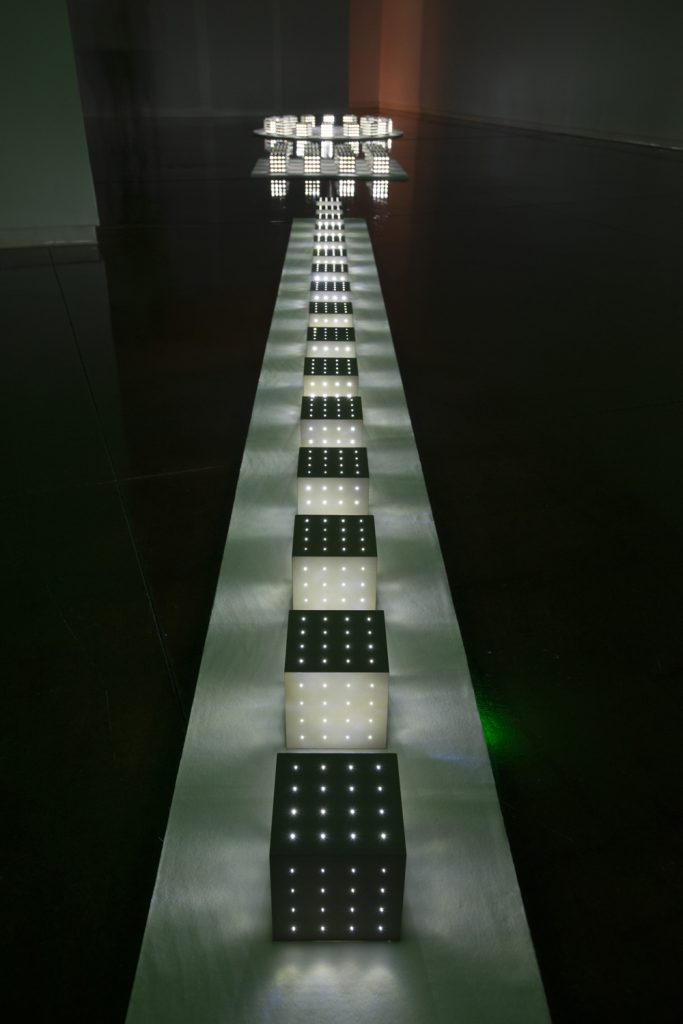

Erwin Redl produces a similar effect with works such as his Fade series, as well as his current installation at the Halsey Institute of Cubes. Works like these invite the viewer in, and by being in the room with the piece they become a part of it. Cubes is a piece that is dependent on its viewership; the space changes and comes alive when people enter and partake in the scene. This dependence allows Cubes to become more than a piece of artwork; it becomes an engaging environment.

During an artist talk, Redl was asked why there was no music playing along with the installation. He responded that adding music would have “dated the space,” allowing too much context to be given to it. For example, if it was accompanied by a Baroque orchestral piece, the viewer could understand it as juxtaposition with the present digital age. If the pieces were paired with electronic music then it would be understood as a work that was meant to have a modern, even futuristic context.

With no music, it’s understood that the cubes stand alone, not tied down by any time period, but as a part of the same space that the viewer inhabits, and it is up to those viewing them to apply their context. A large part of Redl’s aesthetic derives from the minimalists and their pared down approach when making art. In Cubes as well as with his Ascension Circle, he made sure that there are no wires hanging about and that the entire work looked as simple as possible. This attention to restrained structure is shared with minimalists like Fred Sandback. Sandback’s works with colored acrylic yarn in white spaces, while seeming simple in their execution, implore the viewer to not only see the work but also to discern the rest of the form with their minds.

Sandback was also an advocate for people experiencing his works by moving around them, stating that people should seek to actively engage through the space as they walk. Questions of form arise when people don’t understand how something was created. In Redl’s work it could be the question “What powers the fans at the bottom of Ascension?” while in Sandback’s work it could be “How does the yarn stay connected to the floor or the ceiling? Are they using adhesives?” The answer remains the same; the viewer was not necessarily meant to know what goes into the installation, but rather to enjoy and experience the piece as it has been presented to them, even if it boggles the mind.

Sandback was also an advocate for people experiencing his works by moving around them, stating that people should seek to actively engage through the space as they walk. Questions of form arise when people don’t understand how something was created. In Redl’s work it could be the question “What powers the fans at the bottom of Ascension?” while in Sandback’s work it could be “How does the yarn stay connected to the floor or the ceiling? Are they using adhesives?” The answer remains the same; the viewer was not necessarily meant to know what goes into the installation, but rather to enjoy and experience the piece as it has been presented to them, even if it boggles the mind.

Living in the age of technology, where information is shared at a million miles a minute, artists are constantly being exposed to other people’s work, though throughout the ages artists have looked to the work of artists who came before them for inspiration. Redl has been able to take those influences and turn them into something he can call his own. His work holds true to the minimalists’ aesthetic while taking note of light installations that challenged viewers by reimagining their experience of space. In a world of influence, Erwin Redl found his calling.

By Natalie Pagan, Halsey Institute Intern